Textbooks: pricing the future of open education

April 6, 2023

On the afternoon of Thursday, March 30, students, faculty and staff gathered in the library’s Harmon Room to hear a presentation entitled “Textbooks are expensive! How did we get here?” The talk was hosted by Joel Sadofsky ’25, chair of the Academic Affairs Committee (AAC) in Macalester College Student Government (MCSG), Digital Initiatives and Scholarly Communications Librarian at the DeWitt Wallace Library Louann Terveer and associate professor Britt Abel of the German Studies department. The goals of the event were simple.

“We want to sort of help people envision different components of a more just world of open education,” Sadofsky said. “Another big goal of this is to … bring together some different stakeholder groups and different perspectives on surrounding textbooks, … other course materials and open educational resources.”

Sadofsky then explained the data behind exorbitant textbook costs. Stressing that the textbook industry itself is designed in a way that removes options from students, he argued that the cost of textbooks is a “particularly insidious barrier” to accessing a just and open education.

“Textbook selection is not done by those who generally pay the out-of-pocket price,” Sadofsky said, referring to departments making the selection of what textbook to use, then requiring the textbook as a course material. “Because textbook purchasing is often done by students out-of-pocket and selected through departments and faculty, there can be a lack of information as a communication barrier and what that results in.”

Sadofsky cited data that points to five textbook publishers having a stranglehold of 80% of the market, meaning price competition is low and publishers can hike prices. He continued to say that this is particularly problematic when considering how many required textbooks include online modules, which present additional concerns for many students.

“One consequence of [online textbooks] is that [they] can undermine textbook sharing, as well as re-use, and also extralegal measures that students take to acquire the textbooks, which people are often driven to due to the high price,” Sadofsky said.

Another similar problematic phenomenon in the industry is automatic billing that comes wrapped up in programs like Barnes and Noble Inclusive Access, which can not only cost students up to $900 for a whole academic year but also crowd out the potential for the cooperative creation of open-source materials that cost nothing.

It was the rise of these issues that led to the creation of Macalester’s textbook reserve program, run by the AAC, in 2009. The reserve spent $5,000 a semester until the spring semester of 2022, when it spent an additional $1,500, seeing an increased need for free curricular content for students. The reserve targets the acquisition of high-usage textbooks at Macalester that exceed $150 in cost.

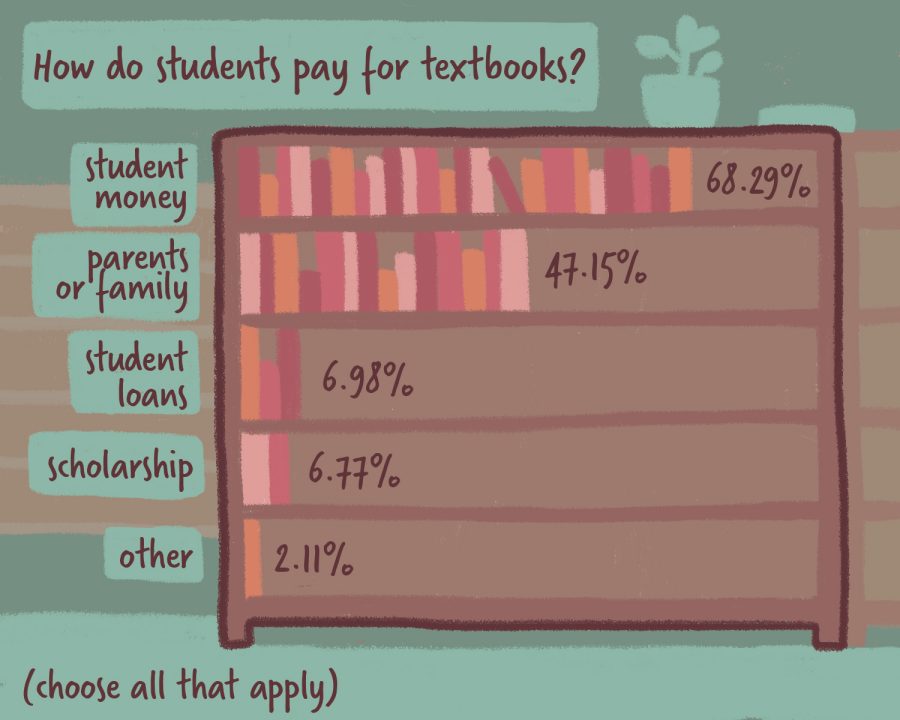

Knowledge of the unique financial needs addressed by the AAC through the textbook reserve program is owed to surveying work done by library staff. Terveer took the microphone next to speak of the results of the most recent student textbooks survey, which was conducted last semester. The survey, which was also conducted by 10 of Macalester’s peer institutions, laid bare systemic inequalities in accessing educational resources.

Terveer read many comments left by students in the survey.

“To be a student at Mac, there is a huge wealth disparity that influences so much of the classroom, including students having to work long hours, to be able to pay for books that they don’t even have time to read after getting home from work,” one such comment read.

Other comments discussed similar experiences, such as dropping classes due to inflated textbook costs or struggling academically due to not having access to required materials. Students also mentioned being forced to use extralegal methods to attain texts, with nearly 40% of respondents saying they’d been forced to not buy a text due to its price.

Even as changes to curricular structuring during the pandemic forced colleges to distribute more accessible and often more affordable resources, students in the survey still reported that they perceived professors caring more about keeping texts affordable than Macalester as an institution itself by a factor of two. Terveer reported that the impacts of this and expensive course materials as a whole, were often more strongly experienced by low-income students.

“Students that had selected the checkbox for ‘Yes, I’m a first-generation college student or a Pell Grant recipient’,… more often selected that there were these impacts such as not purchasing the book struggling academically, not registering for the course,” she said.

Terveer, like Sadofsky before her, hinted that open educational resources (OER) are a more just and sustainable pathway to ensuring students are able to equitably and safely attain textbook access.

To expand on this, Abel told a personal story of her work building an open-access curriculum for her German classes here at Macalester. In 2015, a Facebook post from a German-teaching colleague excoriating socially-conservative attitudes in German language curricula inspired Abel and several colleagues to create a more inclusive and accessible curriculum.

“My colleagues and I were pretty concerned about the cost of textbooks,” Abel began. “We had noticed that students were not purchasing them … We knew our textbook … issued a new edition about every three years without making any substantive changes except to the page numbers so that students couldn’t use used books, right? And we were frustrated with the fact that they weren’t actually addressing the actual problems with the book.”

Beyond this, at the time, Abel was aware of queer elements being removed from textbooks by publishers to appease conservative markets.

“I felt pretty concerned about the gatekeeping of content, and about the lack of being able to move forward and how we represent people in language textbooks because of this,” Abel said.

All of this precipitated the six-year creation of Grenzenlos Deutsch, or German without borders, an online, completely free-to-use curriculum that is quickly gathering momentum among instructors worldwide.

“It’s being used at multiple institutions here in the U.S. and in Canada, and in Australia, because it’s open, and it’s a website,” Abel said. “I know that there are 60 instructors on our shared instructor resources drive, and I’m getting requests [to join] very frequently.”

The creation of Grenzenlos Deutsch and other similar OERs, took a massive amount of labor from students and instructors alike.

“Because this is open, … we had to create our own content,” Abel said. “We couldn’t just go and pull things from the internet or pull things from existing curricula elsewhere, we had to create all our own content. That means all of the videos, all of the images, we had a team of students work on illustrations … and all of those items are artifacts that we created.”

This, in Abel’s opinion, is a potential downside of OERs, especially in comparison to the immense financial and human resources held by monopolizing publishers.

“I just want to make sure you know it takes a lot of money and labor to do a project like this … which perhaps explains why there are so [few] of them out there,” Abel cautioned.

However, OERs clearly improve student experiences. Abel shared survey responses from students who piloted Grenzenlos Deutsch. Students mentioned that the curriculum was extremely easy to use and affirming, and, of course, was free-to-use.

“I get so much feedback from people all over who are using this, that kind of makes me feel like this labor of love is worth it,” Abel said.

After Abel spoke, the presentation was turned back to Sadofsky, who used the last few moments to conclude. Sadofsky urged students to consider the price of textbooks when completing end-of-course surveys in order to give faculty proper feedback that can help to lessen the cost burden on low-income students.

The event was attended by staff from the library and admissions, all of whom must regularly engage with issues of financial access at college. The presentation argued that this is a systemic issue that will not be solved by one college alone. Regardless, context and potential solutions that provide a roadmap for the future were given by all three presenters.

“A very tiny part of the [event] title that I would have added,” Sadofsky said, “[is] ‘where do we go from here?’ I think that’s a crucial part of this.”

Louann B Terveer • Apr 7, 2023 at 1:11 pm

Thank you Jonah, this was a well written account of the presentation!